Scientific Computing Using Python - PHYS:4905

Lecture #22 - Prof. Kaaret

Homework #16 is at the bottom of this page.

Squaring the circle

Numerical integration is the use of an algorithm to calculate the

value of a definite integral. It is also refereed to as quadrature,

which is a historical mathematical term that means calculating area

of a geometric shape by constructing a square with the same

area. The "quad" is the same root that leads us to use the

name quadratic for a polynomial in which the highest power

is a square. People have been working on quadrature since

Babylonian times. There is a papyrus from Egypt from around

1550 BC that states that "a circle's area stands to that of its

circumscribing square in the ratio 64/81". If you think

about this, it means that the Egyptians knew the value of π to an

accuracy of 0.6%.

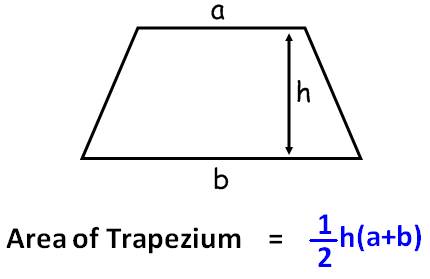

Trapezium

We will consider the problem of finding an approximate numerical

value of the integral of a function f(x), the

integrand, over an interval [a, b],

We evaluate the function at n+1 points equally distributed

in [a, b]. The spacing between adjacent points

is then Δx = (b-a)/n. and the x-values

are xk = a +k Δx, where k

= 0, 1, ..., n.

A simple algorithm would be approximate each interval by a rectangle

with a width of Δx and a height equal to value of the

function at the left edge. This is called a left Riemann

sum. As you can see from the figure below. The left

Riemann sum is not a great way to calculate an integral. It

works if you make your bins fine enough (at the cost of more

computations), but it underestimates the integral in regions where

the function slope is positive and overestimates it where the slope

is negative. One could instead use a right Riemann sum, taking

the function value at the right edge, but it has the same issues,

only reversed.

A better thing to do is to use a trapeze. Oops, that's for the

circus. I meant a trapezium. The Trapezium is a tight

open cluster of stars in the heart of the Orion Nebula, named for

its four brightest stars.

Trapezium is also the word used in English outside North America to

denote a convex quadrilateral with at least one pair of parallel

sides. Most of us in this class call such an object a

trapezoid.

Trapezoids offer a more accurate way to estimate an integral.

The idea is that rather than draw a rectangle with a height set by

the function value at one edge, let's draw a trapezoid between the

two edges. For reasonably smooth functions, this often

provides a nice approximation to the function, and therefore a more

accurate estimate of its integral.

The area of a trapezoid is (a+b)h/2, where h is its height and a and

b are the lengths of the two sides.

We'll flip the trapezoid on its side, so that

.

The area of each trapezoid is then .

To calculate the integral, we sum the areas of all of the

trapezoids. For the first trapezoid, we'll have

When we add in the second one we get

Adding the third,

Note that we have to pay special attention to the first and last

points because they only contribute to one trapezoid while all of

the other points contribute to two.

Our approximation for the integral is then

Doing numerical integration this way is called using the trapezoid

rule and this formula is called the extended trapezoid rule.

We can write a Python function to do numerical integration via the

trapezoid rule using the following steps.

- Take as input, the name of the function to be integrated (f),

the endpoints of the interval of integration (a, b),

and the number of points to use (n).

- Create an array with xk values evenly

spaced from a to b.

- Evaluate the function at each xk value.

- Evaluate the sum in the equation above.

- Return the sum multiplied by the spacing between the points as

an estimate of the integral.

Thomas Simpson's rule

Approximating our function with trapezoids is nice, but it misses

sometimes, particularly if there is a maximum or minimum between our

x-values or the function has curvature. The trapezoid

rule approximates the integrand by drawing a line between adjacent

pairs of points. Instead, we could take adjacent triples of

points, draw a parabola through those three points, and integrate

that parabola analytically. This often does a better job as

nicely shown the figure below (drawn by Popletibus),

The formula for the area for one interval is

Note that if you substitute x0 = donut, x2

= beer, f(x)= Homer(x), you can re-write this

as Homer Simpson's rule,

To calculate the integral, we sum the integrals of all our little

parabolas. Note that we move by 2Δx each time so that

successive integration intervals don't overlap. The extended

Simpson's rule for calculating an integral is

The coefficients alternate between 4 and 2 all the way through the

middle of the sum. Note that n needs to be an even

number so that we have an odd number of terms in the sum.

The algorithm for doing integration via Simpson's rule is very

similar to that for the trapezoidal rule, but the sum is different.

Higher power?

You might ask, why stop at quadratic polynomials? There is a

Simpson's rule that uses cubic polynomials and the so-called

Newton–Cotes formulae allow any degree of polynomial. However,

one reaches diminishing returns because high order polynomials tend

to oscillate around the points they are drawn through and don't

actually provide better approximations. This is especially

true if the function has jumps, as seen in the figure below that

shows approximations to a step function with polynomials of 3rd,

5th, and 7th order and with the trapezoid rule. The trapezoid

rule clearly does a better job.

In general, numerical integration methods tend to work well for

smooth functions and poorly for functions with sharp features or

oscillations over scales close to the integration step size (Δx

in our discussions above). If your function has one or a few

discrete steps at known locations, then it is better to break the

integration up into pieces with edges at the step locations.

If your function oscillates, then you need to have at least

several integration bins within each oscillation period.

Adapt or perish

The accuracy of our estimation of the integral using either the

trapezoid rule or Simpson's rule is essentially set by the number of

grid points. More points means a smaller step size leading to

a better approximation of the function. The method don't

include a means to estimate the accuracy of the integration because

that depends on how well they approximate the function, which is

impossible to know precisely unless one can evaluate the integral

analytically, in which case one should do that rather than doing a

whole bunch of computations, or one evaluates the function at all

points in the integration interval, which would take an infinite

amount of time.

Usually, one estimates the accuracy by comparing the numerical

estimates obtained with different grid spacing. E.g. find the

integral using 1000 grid points, do it again with 2000 grid points,

and then take the absolute value of the difference as an estimate of

the accuracy. If the integrand is relatively smooth, so higher

order derivatives are not too large, then the accuracy of the

trapezoid rule scales with while

the accuracy of Simpson's rule scales with

.

You will check this in the homework assignment below.

In adaptive quadrature, the algorithm adjusts the grid to

obtain the desired accuracy. In simplest adaptive quadrature

algorithm, one

- Chooses an grid size and applies a method like the trapezoid

rule or Simpson's rule to estimate the integral. We'll

call the value of the integral I0.

- Divides the step size in half and repeats the numerical

integration. We'll call the new value of the integral I1.

- Checks if the desired accuracy has been reaches, specifically

check if abs(I1 - I0) <

itol*abs(I1), where itol is the

desired fractional accuracy. If we have reached the

desired accuracy, then we are done and we return I1.

If not, we set I0 = I1

and go back to step 2.

Such algorithms are called "globally" adaptive because they adjust

the whole grid. The trapezoidal rule and Simpson's rule are

particularly useful because we get to re-use all of the function

evaluations as we make the grid finer by dividing the step size in

half. The trapezoidal rule is particularly computationally

efficient because we don't even have to redo the sum over those

points.

becomes

We can simply add the old sum to the new sum with the new

points. We don't even have to keep the values from the

function evaluations on the coarser grid.

The disadvantage of globally adaptive quadrature is that the finer

grid spacings can become computationally expensive. In locally

adaptive quadrature, one breaks the interval into pieces and refines

the grid only for the pieces where the integral is not sufficiently

accurate. For example, one might

- Evaluate the integral in the intervals [a, (a+b)/2]

and [(a+b)/2, b], i.e. divide the original

interval in half, using a step size of Δx.

- Evaluate the integral in the same intervals using a step size

of Δx/2.

- For each of those intervals, check if we have reached the

desired accuracy using the same equation as in step 3 for global

quadrature. Note that if we achieve the desired fractional

accuracy in all intervals, then we will achieve it globally.

- For any interval where we have reached the desired accuracy,

stop and record the integral for that interval. For any

interval where we have not reached the desired accuracy, split

that interval into two pieces by going back to step 1 with a

and b set to the edges of that interval.

Some locally adaptive quadrature algorithms have an additional check

and stop if the global accuracy of the integral is good enough, i.e.

they add up the contributions from all of the pieces at each step

and stop if estimate of the total integral changes by less than itol

even if that accuracy hasn't been achieved for each individual

piece. This keeps the algorithm from throwing computational

resources into small pieces of the interval that are poorly behaved,

but don't make a large contribution to the total integral.

Locally adaptive quadrature is rather more complex to program than

globally adaptive quadrature. Most people don't even try, but

instead use a software package called QUADPACK that

was written in Fortran in the 1980s. There is a 300 page book

describing QUADPACK. Fortunately, the SciPy library includes

an interface to QUADPACK. The routine scipy.integrate.quad

uses locally adaptive quadrature to numerically integrate a

function, f(x), in a given interval (a, b),

to a specified relative accuracy epsrel, which is set by

default to 1.49e-08. It returns the value of the integral and

an estimate of the error. An example calling sequence is

from scipy.integrate import quad

integral, integral_err = quad(f, a, b)

The routine has many optional parameters and many more variables

that it can return that are described at its reference page https://docs.scipy.org/doc/scipy/reference/generated/scipy.integrate.quad.html.

There is also a version to do double integrals of functions with two

variables, scipy.integrate.dblquad.

Homework #16

For HW #15, you will write Python code to perform numerical

integration via the trapezoid rule and Simpson's rule and evaluate

the accuracy of those routines. Please hand in your code

electronically.

Your code should have a function integrate_trapezoid that

does numerical integration using the trapezoid rule and takes as

input: the name of the function to be integrated (f), the

endpoints of the interval of integration (a, b), and

the number of points to use (n). Write this function

first and test it by integrating

over the interval [0, 10], which you should be able to check

analytically. Your code should have a similar function integrate_simpson

that does numerical integration using Simpson's rule.

In the main body of your script, define the function

g(x) = (1+cos(x)) * exp(-x/(2*pi))

First plot this function over the interval x = [0, 60].

Then write a loop that integrates this function in the interval [0,

60] using different values for the number of points,

where j = 6, ... 16. Do the integration using both the

trapezoid rule and Simpson's rule.

For each n, plot the error in the numerical integration,

which we will define as the absolute value of the difference between

numerically calculated integral and the analytically calculated

integral which is

versus the integration step size, Δx. You should do

this on a log-log scale. Think about what trends you

see. In particular, does the error for each method depend on

some power of Δx? Include a comment block at the end

of your code with some discussion of this.

This assignment is worth 50 points.