The website for the class is https://homepage.physics.uiowa.edu/~pkaaret/2019f_p4905/index.html

The syllabus is at https://homepage.physics.uiowa.edu/~pkaaret/2019f_p4905/syllabus.html

The required textbook is the Updated edition of A

Student's Guide to Python for Physical Modeling by Kinder

and Nelson. How many of you have the textbook with you

now? You should bring the textbook to each of the next

several lectures.

The Linear Algebra textbook for the course is Linear Algebra

by Cherney, Denton, Thomas, and Waldron. It is available for free

at https://www.math.ucdavis.edu/~linear/.

Another linear algebra resource is Linear Algebra: A Course

for Physicists and Engineers by Mathai and Haubold. This

book is available electronically for free via the UI Libraries at

https://www.degruyter.com/viewbooktoc/product/495839.

Python 3.7 is installed on the computer in front of you.

Please log in now, it can take a while. If you prefer to use

your own computer, install Anaconda Python 3.7 from https://www.anaconda.com/dow

What do you do when you program a computer?

Usually, programming is described as writing down a set of

instructions for the computer to execute. That is correct,

but leaves out an equally important part of programming, which is

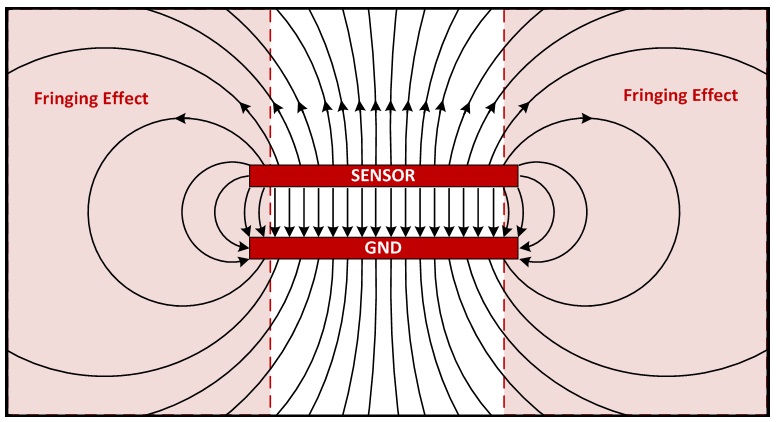

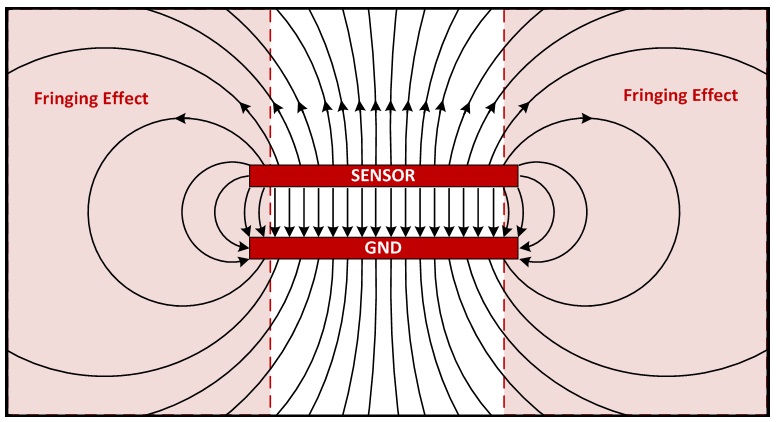

thinking up appropriate data structures. Say you want to

calculate the electric field between two parallel plates.

What sort of data structure do you need?

The textbook refers to this as 'the state' of the computer.

At a fundamental level, programs read and modify the contents of

memory cells in the computer. Fortunately, programming

languages like Python abstract away from these low level details

and allow us to think in terms of data structures like vectors and

matrices.

On your computer, startup Spyder by going to Windows Menu, Anaconda, then Spyder. We will be using Spyder a lot, so before you might want to right click on it and do "Pin to taskbar".

Spyder has several panes. For today, we'll be using the

Console pane. In the Console pane, type

x = 2

x = x+1

x

Most programming languages use the = sign as an assignment

operator. The variable named on the left side of the = is

set equal to the value of the expression on the right side of the

=. It is ok to have the same variable on both sides of the

=. In normal math, the second line would make no sense, but

in Python it means add one to the current value of x and replace

the contents of x with that sum.

If you want to check if two expressions are equal, then you need

to use the operator ==. Type

2 == 2

You should get the result True. Type

2 == 1

You should get the result False.

Note that Python can use logical or Boolean values

(True/False) for variables as well as numerical values. Try typing

a = True

a

The console should print out True.

Python uses two different types of numbers, integers and floating

point numbers or 'floats'. Integers do not have a fractional

part. They are often more compact to store in memory and are

faster to do operations with than floats, so they are often used

for efficiency. Also, there are some situations where it

doesn't make sense to use a number with a fractional part, e.g.

choosing the nth entry in a vector, so Python

requires use of integers in those cases. Python decides

whether a variable should be an integer or float based on the

number that you assign to it.

a = 1.4

makes a a float. While

a = 14

makes a an integer.

c = 4+5j

The exponentiation operator in Python is **, so to square a

number, you do x**2. Try

c**2

Do you get the answer that you expect for a complex number?

How about if you try

c*c.conjugate()

Python can also use 'strings' to represent text. Type

s = 'Hello'

t = 'there'

s+t

You should get 'Hellothere'. It is possible to manipulate

strings, but some of the operators have different behavior than

for numbers.

Python has two major versions Python 2 and Python 3. The

two versions of Python are not quite compatible. It is best

to learn Python 3 because Python 2 will not be maintained past

2020. There is even a website counting down to the end of

support for Python 2 at https://pythonclock.org/.

The textbook is written using Python 3. The Physics

computers have Python 3.7 installed.

One of the biggest differences between Python 2 and 3 is how they

handle division of integers. Type

3/2

You should get 1.5. If you get 1, then you are using Python 2. In Python 2, when you divide two integers you get an integer back, which drops any fractional part of the answer. In Python 3, when you divide two integers you get a float back.

If you are running Python 2 and want to make it compatible with Python 3, you can do so by including a few lines of code at the start of each session and at the top of every Python program. Note that you do not need to do this on the computers in the lab or any other computer running Python 3. The two lines are

from __future__

import division, print_function

input = raw_input

We can set up Spyder to add this automatically to any program we write using the Spyder menu. Do Tools/Preferences/Editor/Advanced and then click on 'Edit template for new modules' and add the two lines above below the last line.

We can also set up Spyder run these lines automatically in the

console. Do Tools/Preferences/IPython console/Startup. Then in the

box 'Lines', type the line below.

from __future__

import division, from

__future__ import print_function, input = raw_input

These customizations of Spyder will also be useful when you start

programming. You will likely want to include more lines for

both the console and editor after you have seen what libraries you

use on a regular basis.

Python has relatively few built-in functions, but there are many libraries of useful functions written in Python and publicly available. The most important library for us is NumPy which is a numerical processing library and implements functions like sqrt (for square root), values like pi, and data structures like vectors and matrices. You tell Python that you want to use a library by importing it. Type

import numpy

You should then be able to type expressions like

numpy.sqrt(2) and numpy.pi.

It is inconvenient to always have to type out numpy, so Python allows you to import the numpy library and give it a different name. Type

import numpy as np

Then try np.sqrt(2) and np.pi. The textbook uses

this as its standard way to import the numpy library and the

examples in the text assume that you have previously done 'import

numpy as np'. You might consider adding this to your Spyder

startup.

Some of us are very lazy and find typing even three characters too troublesome. Python also enables this level of laziness. Type

from numpy import

*

Then try sqrt(2) and pi. Finally, one has made

Python look like the scientific programming language that it

should be. However, importing all of the functions from

numpy can create issues if you or another library that you have

loaded has functions with the same names. In this case, you

can limit the number of functions imported by using a line like

from numpy import

sqrt, pi

In this case, Python will import only the selected

functions.

The remainder of today's class will be devoted to learning the

basics of Python by working through the first chapter of the

textbook. As you read the chapter, enter the commands in the

purple highlights into Spyder and see what you get. When you

are done with the chapter, do the first assignment which will be

due at the start of the next class. If you are already

comfortable with Python, feel free to move directly to the

assignment. Also, please do the reading for the next class before

class on Thursday.

HW #1 is due at the beginning of the

next class. For the first couple of weeks of this

class, there will be a homework assignment for each class that

will be due at the beginning of the following class. The

reason for this is that each class builds directly on what has

gone before and you really need to do programming yourself to

figure out how it works.